Choeung Ek Killing Fields

This was arguably the hardest day of my trip, emotionally.

Indeed, being lost among the marvels of Cambodia’s ancient past in the temples

of Angkor Wat, or dealing with ever-smiling Cambodians can never prepare your

heart to relate to the horror of the country’s recent events. So, before

starting my tale, let me (very briefly) introduce you to this particular little

bit of history.

During the course of the Vietnam War, fought between South

and North Vietnam and with extensive involvement of foreign allies on both

sides, conflict and fighting (and bombing) spread to the neighboring countries

of Laos and Cambodia, leading to the creation, in the latter, of the Khmer

Rouge (Red Khmer) – a communist radical insurgency group. Khmers are the

majority ethnic group in Cambodia. Led by the revolutionary leader Pol Pot,

this group fought a gradual guerrilla war against the government forces, being

backed up by communist forces of North Vietnam and the Viet Cong. The Khmer

Rouge took power in Cambodia after seizing the capital, Phnom Penh, in 1975.

Pol Pot wished to create a pure agrarian communist state in

the country. Being suspicious of city-dwellers (regarded as parasites and

lackeys of capitalism), he ordered the immediate evacuation of cities. In three

days, the entire population of Phnom Penh (between 2 and 3 million) was ordered

to move out and assigned to 12-hour-a-day forced labor in farm fields. As Pol

Pot’s regime developed, violence against perceived “traitors of the revolution”

escalated, leading to the creation of prisons, torture chambers and,

ultimately, killing fields all over the country. An estimated 3 million people

(out of a former population of 8 million) died under the rule of the Khmer

Rouge.

For more information, I recommend the good Wikipedia

articles on Pol Pot, the Khmer Rouge, and Democratic Kampuchea. I also highly

recommend watching the 1984 movie The Killing Fields. So, upon arriving in

Phnom Penh, I decided to visit one of the killing fields and the most famous

political prison, to have a deeper understanding of that sad bit of human

history.

The Choeung Ek Genocidal Center, created upon one of the

killing fields in the outskirts of Phnom Penh, first impressed me by how lovely

the place is. It was a sunny day, the place is clean, verdant and pleasant, and

not at all what one would expect of such a location. On the front, there is a

high memorial stupa. This quickly brings you back to reality – the stupa houses

an incredibly high pile of more than 5,000 human skulls, part of the over 9,000

bodies found in that field alone. More on that later.

|

| The memorial stupa |

Choeung Ek wasn’t a concentration camp, as there was no

forced labor here. One entered the place either to kill, or to die. The aim was

to eliminate prisoners as quickly and efficiently as possible. The method was

mainly bludgeoning, since the Khmer Rouge wouldn’t spend precious bullets for

such a job. Executions were conducted only at night, to avoid raising suspicion

of people and workers nearby. Prisoners would be walked to previously dug

collective pits, killed on the spot, and thrown in the pit, much in the way

illustrated below.

There are signs marking the places where the buildings

(later destroyed by the Vietnamese) were. Two of them are particularly

touching. During the height of its activity, more than 300 prisoners were

executed every day here, more than the guards could handle. So a small prison,

dubbed “the Dark and Gloomy Prison” was erected – just a windowless depot for

storing human cargo to be executed during the next night. There was also a

storage room for chemicals – those helped cover up the unbearable stench, and also

served to kill any half-dead prisoners thrown in the pits while still alive.

Perhaps the best image of the Khmer Rouge’s utter disregard

for life is provided by their own famous saying, aimed at the traitors: “To

destroy you is no loss. To preserve you is no gain.”

There are many, many depressions in the soil around the site.

These mark the former pits. The bodies were exhumed and moved to proper burial

sites. However, during every rainy season the waters and erosion bring up

fragments of bones, teeth, and cloth rags. Indeed, you can see many of them in

the ground around your feet, one of the gloomiest visions I ever had. It’s

almost as if the place itself will not let anyone forget the horror that

happened here.

There is also a very good audio tour provided along with the

entrance ticket. You can hear explanations about each part of the place, as

well as stories from survivors of the Khmer Rouge’s prisons and camps. There

are no survivors from Choeung Ek. It’s impossible not to be moved by the

stories, or to to fight the tears as you try to imagine what it must have felt

like to go through all of this. Suddenly, all your problems, suffering, and

everything you ever thought hard or painful in your life seem small and

insignificant – and they really are.

|

| Bones collected from the ground |

|

| On this tree a huge loudspeaker was hanged every night, playing political songs, so as to disguise the place as a Khmer Rouge political meeting, and muffle the screams of the victims. |

One of the most terrifying visions was the tree below. Here, the

children and little babies of prisoners were killed. Standard procedure was to

hold the child by the ankles, and then smash his/her head against the tree. The

horror is simply unspeakable.

By the end of the circuit, you can visit the memorial stupa.

Here, layers upon layers of skulls retrieved from the pits are kept. This is

truly a terrifying vision. The skulls are just there, each of them belonging to

a person who was once just like you and me – good and bad, loving and selfish,

generous and greedy, all of them stripped from the greatest gift of them all. They

are all just there, looking back at you, as if demanding answers for the horrible

crimes committed against them.

So after all this, deeply upset and lost in thoughts, I

decided to look for a restroom. Found one near the museum bordering the walls.

After getting out, I heard a lot of laughter and happy, playful sounds. I

looked over the wall:

Just beside the memorial there is a school for small children. There

they were, doing that wonderful mess children do, completely oblivious to the

terrible deeds that happened next door. Probably some of their relatives even

were here. I found new hope upon seeing the school – there is the future of

Cambodia, and I pray those children can build up a society that learns, and

remembers.

Tuol Sleng (S-21) Prison

Most of the prisoners executed at the Choeung Ek killing

fields were first detained at the S-21 Prison. This place was a high school

before the Khmer Rouge took power. After that, all schools in the country were

simply closed, as Pol Pot believed education was useless to the revolution, and

corrupted the purity of the “old people”, the pure, agrarian peasant lifestyle.

The building was renamed Security Prison 21, and turned into a prison and

execution center for political targets, right in the middle of Phnom Penh.

Right in the front of the main courtyard, that looks just

any other school grounds in the world – classroom buildings surrounding big

playing fields – are the tombs of the 14 last victims of the center, the ones

whose corpses were found there when the place was liberated by the Vietnamese. Between

17,000 and 20,000 people were imprisoned in Tuol Sleng, and out of those there

are only 7 survivors, all of whom had some skill useful to their captors, such

as painting or photography. Right there is also a big sign stating the code of

conduct of the center.

One of the buildings was used as a detention unit, with

wooden and brick cells adapted within the former classrooms.

In the detention building there is barbed wire in every

open-air corridor. This was to prevent prisoners from committing suicide by

jumping down.

The other building was used as an interrogation facility.

Prisoners would be extensively tortured to reveal names and locations of

friends and family, who would in their turn be arrested, tortured and sent to

the killing fields.

|

| Looks like a regular school... |

|

| One of the interrogation rooms, and a picture of how it was found |

|

| These poles were used by students for exercise, but the KR adapted them for torturing people by hanging them upside down into water containers |

|

| The torture tools |

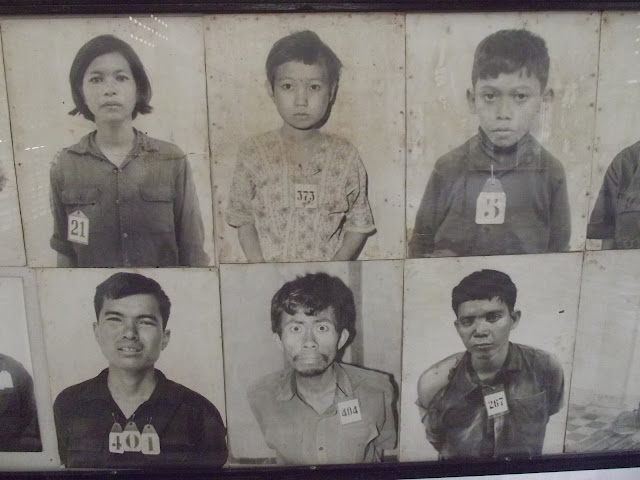

The Khmer Rouge, in an upsetting similarity with the Nazis,

were extremely meticulous in recording all their activities. Prisoners were

measured, photographed, given identification numbers and photographed again

after torture and death. Lists would be checked and rechecked everyday to

ensure that nobody escaped. Confessions, completely made-up and gotten under

extreme torture, were written down and signed by the prisoners, who were then signing

their own death sentence.

|

| One of the prisoners actually smiled for the photo. I'm still wondering about what caused that smile. |

|

| Can you see the traitorous look of these children? Such a threat to the revolution. |

|

| Some of the prisoner profiles and confessions |

There are plenty of photos of the bodies after torture in

the Khmer Rouge’s archives, but I really couldn’t bring myself to photograph

them.

I left S-21 with a bleak feeling about humanity. Perhaps the

best question was one I’ve found on the walls of one of the cells in the

detention building. Some previous tourist, doubtlessly assaulted by the same

feelings I was experiencing then, wrote:

“Will we ever learn?”